This is the transcript of an address given 13 Nov 2014 at the Belkin Gallery in Vancouver.

—

Thanks everyone for being here. And thank you Shelly Rosenblum and the Belkin Gallery for inviting me.

I’ve only been full-time faculty here for 18 months or so. And one thing I didn’t know to anticipate were these cross-disciplinary conversations that were possible on-campus. Last week I enjoyed listening to novelist Camilla Gibb talk at the Peter Wall Institute about empathy and anthropology. Today I get to talk with UBC History professor Carla Nappi about Ai Weiwei. This is a great pleasure.

I’m going to avoid saying anything that might be mistaken for art criticism today. It’s not my field. What I’m going to do instead is draw on my own practice area – both in journalism and writing novels – and talk about the narrative that these images suggest to me.

I feel encouraged to do this by Ai Weiwei himself, who didn’t really consider this collection of photos to be a work of art in themselves. This will seem counterintuitive, I realize. Ai WeiWei is one of the most recognized contemporary artists in the world today. He curated this selection from 10,000 original pictures and took the time to put them in a particular order. And of course it’s hanging in an art gallery, so it must be art.

But what he actually said about this collection is: “I would not consciously have called it art. It’s just the activities in my life. Becoming more conscious of my life activities, that attitude was more important than producing work.”

The attitude Ai Weiwei was speaking about was the conviction that he was indeed an artist, a belief that everyone who wants to practice in the arts must somehow attain. Not trying to be an artist. Not planning. But being. With these photographs, Ai Weiwei seems to be telling us, he wasn’t making art, he was making himself as an artist, which is never easy.

As a storyteller, I find that very interesting. Narrative comes to life when three elements first combine: (1) character, (2) desire (for concrete or abstract outcomes), and (3) obstacles that prevent the character from merely claiming what is desired. That’s the juice of narrative right there.

And as I look at these photographs, that’s what I find myself seeing. The beginning of a narrative about Ai Weiwei’s movement towards an objective. He may be a superstar now. But these pictures offer a glimpse of Weiwei at his crucial moment of becoming. 25 years old, out of China for the first time, and for the first time also engaged in a fully autonomous way with his own dreams and desires.

So who was this young man, before becoming the famous man?

History is relevant here. Born in 1957 in Beijing, Ai Weiwei arrived just a few months after his father, the well-known poet Ai Quing, had been denounced by authorities, banned from writing or publishing. And the family had been sent to a work camp in Northeast China. The cultural revolution in 1966 arguably made things worse for them. And without dwelling overly on this history, just consider that Ai Weiwei as a nine year old boy saw his father publically and ritually and repeatedly humiliated. He saw posters with his father’s image and defamatory statements. He saw his father force-marched through the streets, chanting confessions to crimes he hadn’t committed, while children threw stones. In a particularly vivid memory, the artist remembers when his father was denounced as a “reactionary novelist” by people who knew nothing about his father’s writing – he was a poet, and had never written a novel – and these people then doused his father’s face in black ink. Since the couldn’t afford soap, his father’s face remained black for many days.

The end of the Cultural Revolution didn’t heal everything either. “After 20 years of injustice,” he said. “We were given only these words: it was a mistake.”

They were back in Beijing however, and more free than ever before. Ai Weiwei joined the Beijing Film Academy in the Set Design department, where he was going to learn how to paint. But almost immediately he began producing work so outrageous to his instructors that they declined even to consider it for grades. Ai Weiwei eventually quit and applied to study abroad in the US.

So that is the young man who arrived in the East Village in 1981, working part time jobs and by his own description, not really having any solid idea what he was doing there. He speaks of just leaving his apartment in the morning and wandering, without direction or agenda.

But he did have a vision of himself as an artist. And so a crucial triangle takes shape: a character, desire, and all the many obstacles that you might imagine for a broke, new immigrant, shortly to be an illegal immigrant, who has this most impossible of dreams.

Luckily for us, he also had a camera with which that narrative beginning might be captured.

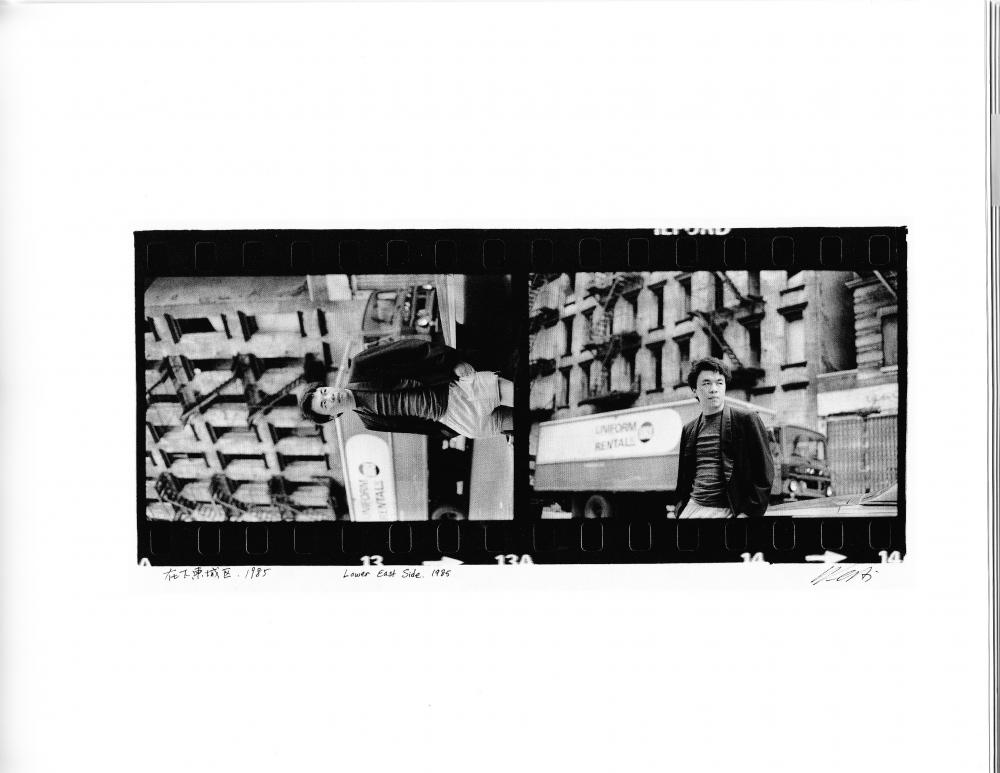

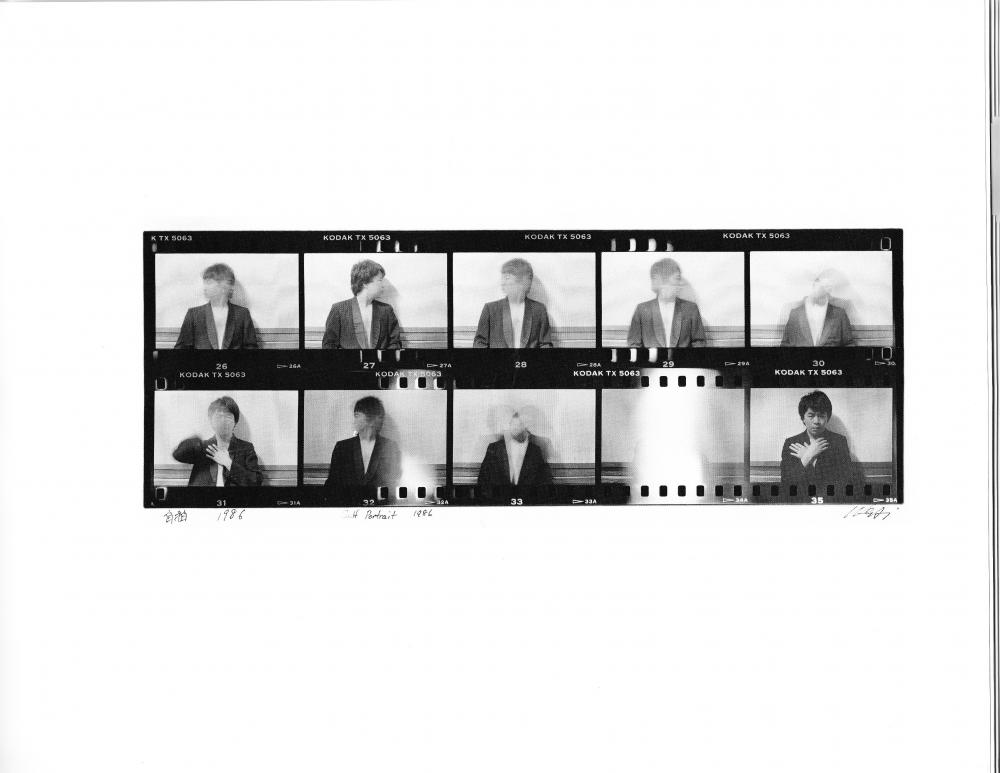

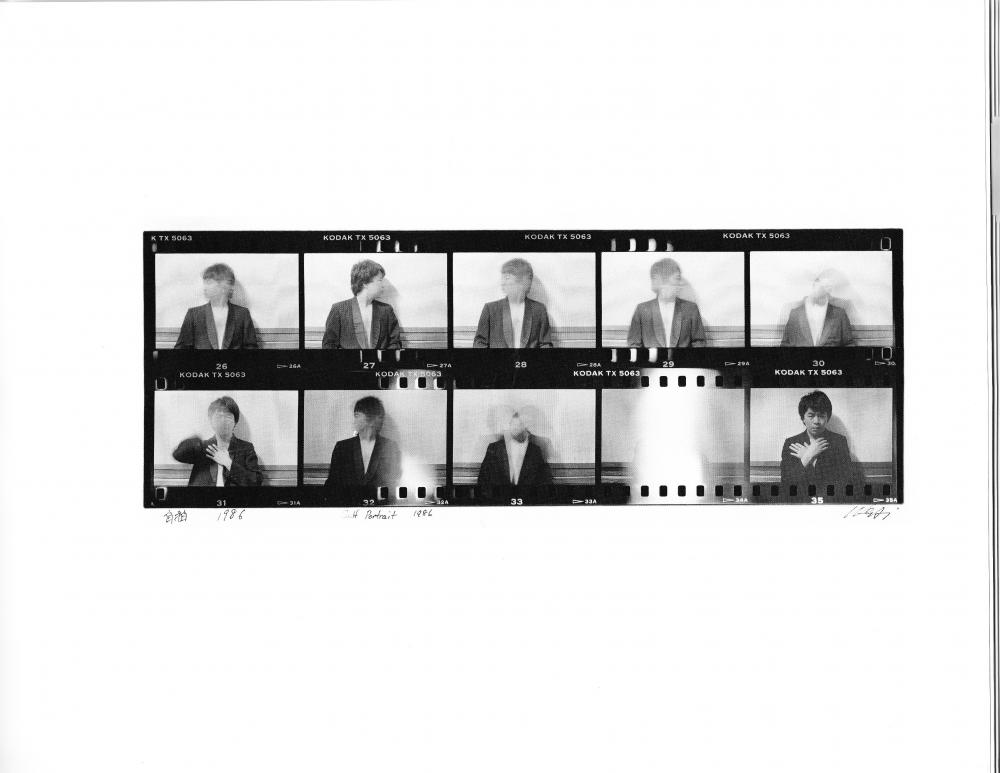

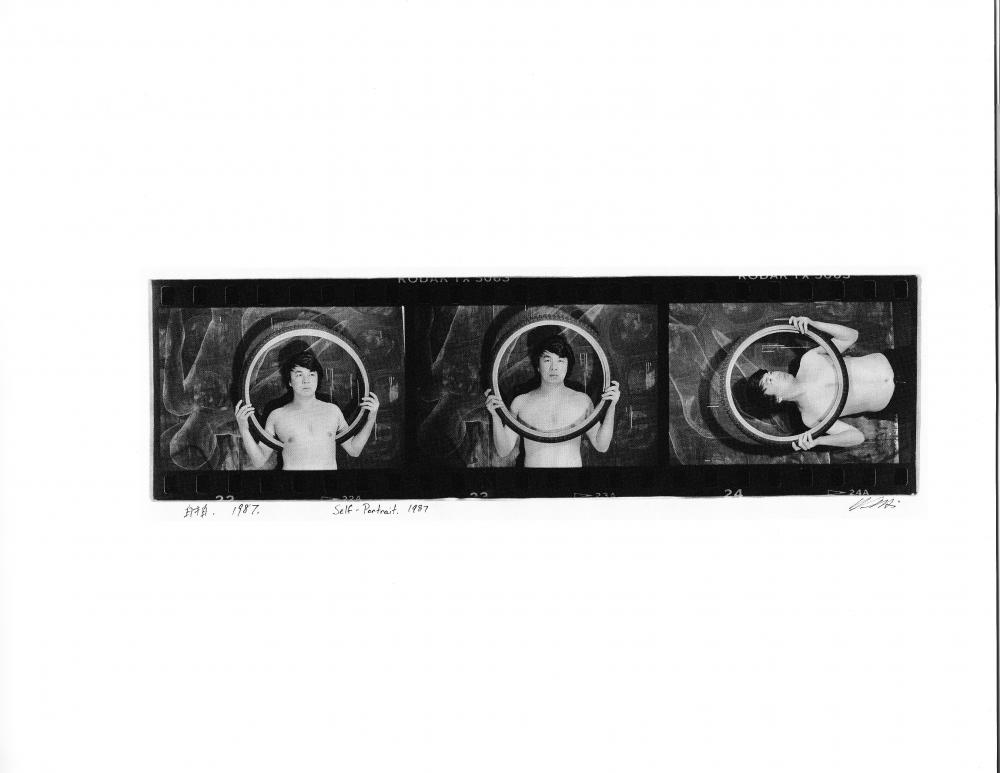

Not immediately, however. But it seems that around 1985, or 1986, the photos really started to accumulate. This documenting of himself doing the thing he’d dreamed of doing.

Here’s the son of a poet who was forbidden to write for twenty years. Here’s an artist declaring himself to be subject to no such powers.

“I started my own life, in which I was very clear about my own decisions. Before that, I was a student and all the decisions were made by common requirements – you study at school, finish your studies, and then try to become an artist. Then I realized that I am an artist and that it’s my life and that’s the way I choose to live. So I started to take some photos… excited about this new life and this kind of attitude.”

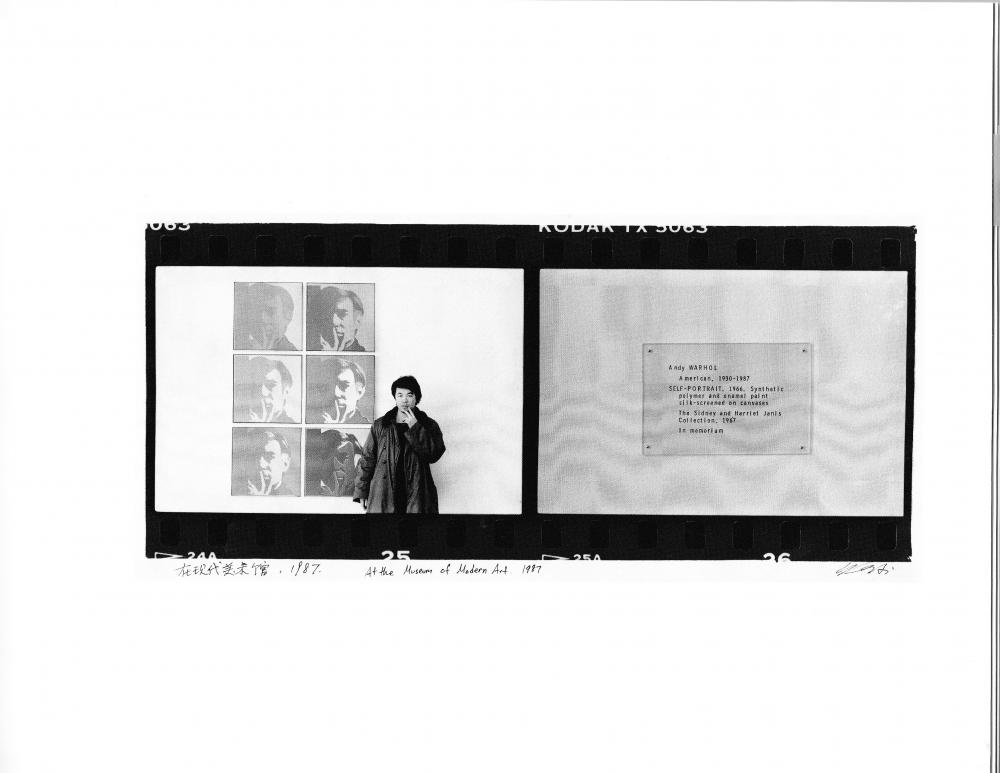

No surprise then that Ai Weiwei developed what you might think of as the proto-selfie. Here he is at the MOMA

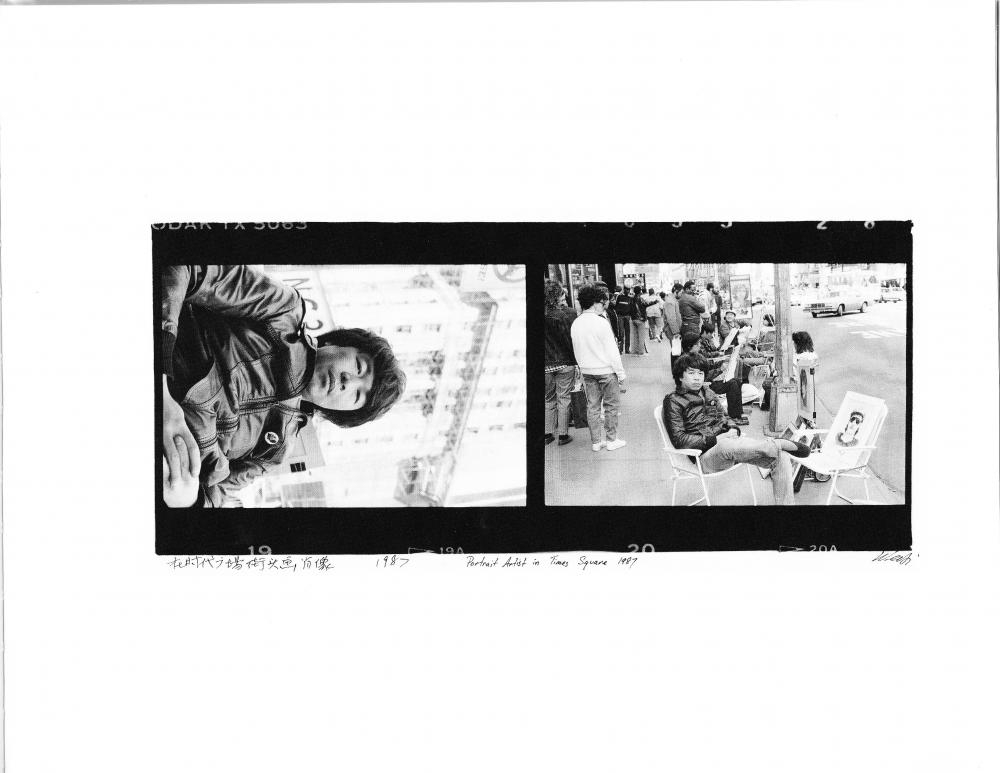

Here he is on West Fourth Street, where Ai Weiwei and other Chinese artists would paint the portraits of passersby.

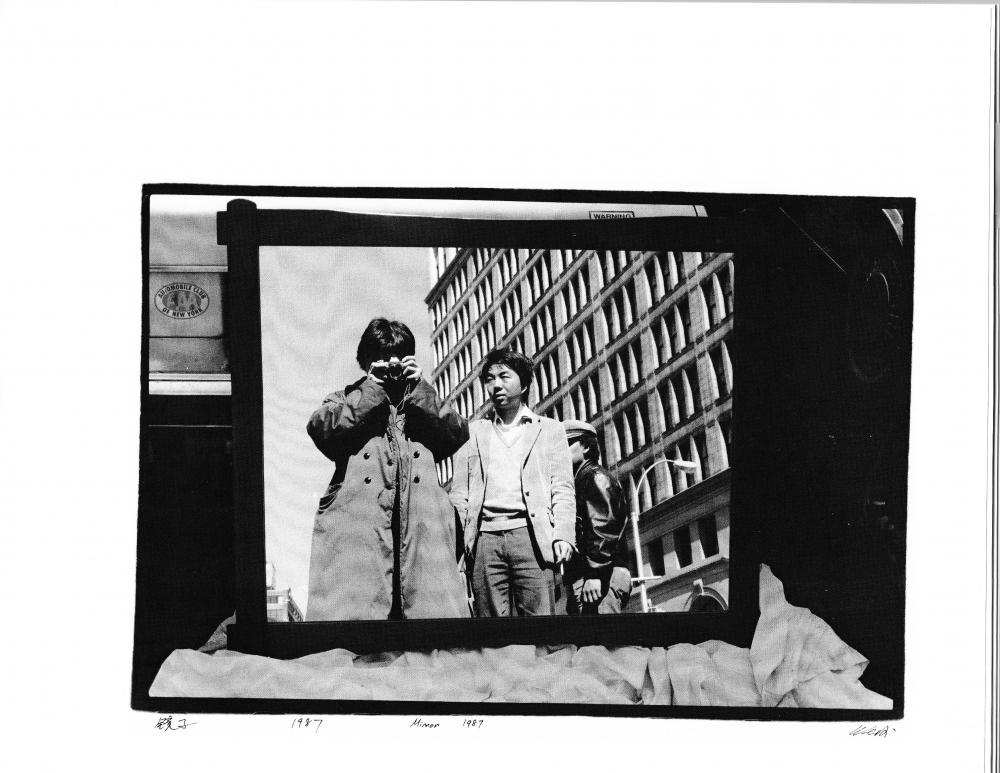

The artist here is in the process not so much of examining himself as gathering the supporting evidence to prove himself, something this shot into the mirror really captures.

That’s Ai Weiwei recording Ai Weiwei in the process of becoming Ai Weiwei.

In the Facebook era, there is a tendency to dismiss this as self-promotion: fatuous and transparent. But here is a man raised on the edge of a northern Chinese desert, exposed for the first time to the possibilities of the individual. I find this mirror shot makes a lot of sense in that context.

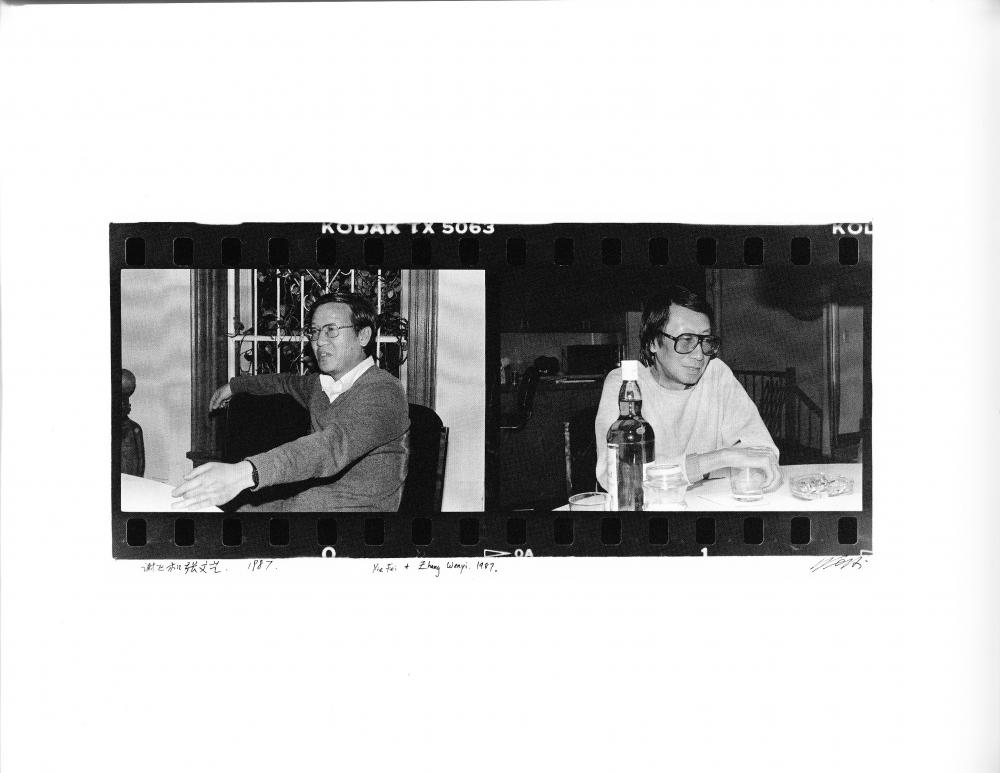

Of course, it’s important to understand that he wasn’t an isolated loner as these images might suggest. Selfies run the risk of suggesting total self-absorption. But this doesn’t appear to ahve been the case. In fact, Ai Weiwei seems to have been a social magnet during this time, constantly in touch with people, exploring, listening, exchanging ideas. One imagines the conversations to have been very lively.

Artist and intellectuals:

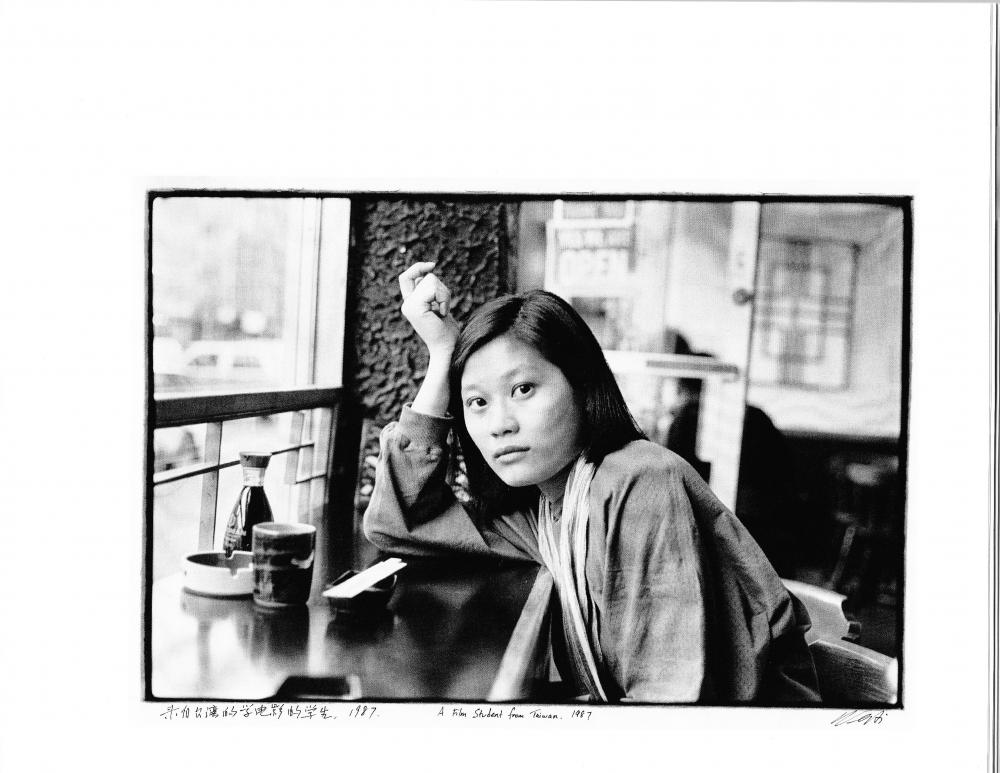

A film student from Taiwan.

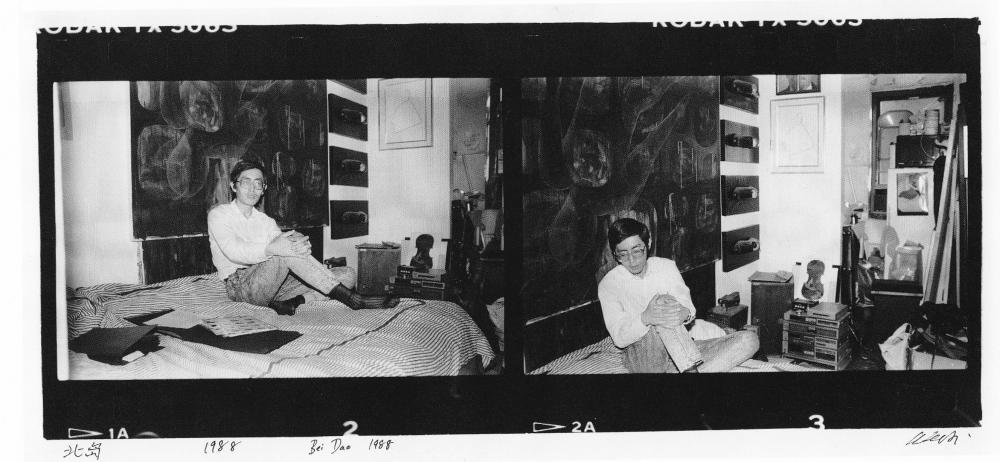

Here’s the well-known Chinese poet Bei Dao visiting with Ai Weiwei in 1988.

Bei Dao is the most notable representative of the Misty Poets, a group of Chinese poets who reacted against the restrictions of the Cultural Revolution. Dao would go on later to write a book of essays about his time in New York called Midnight’s Gate which includes a cloaked reference to Ai Weiwei.

In a piece in Artforum, Philip Tinari writes: “Everyone in Bejing knew that his basement apartment on East 7th Street had become an unofficial embassy for the avant-garde in exile.”

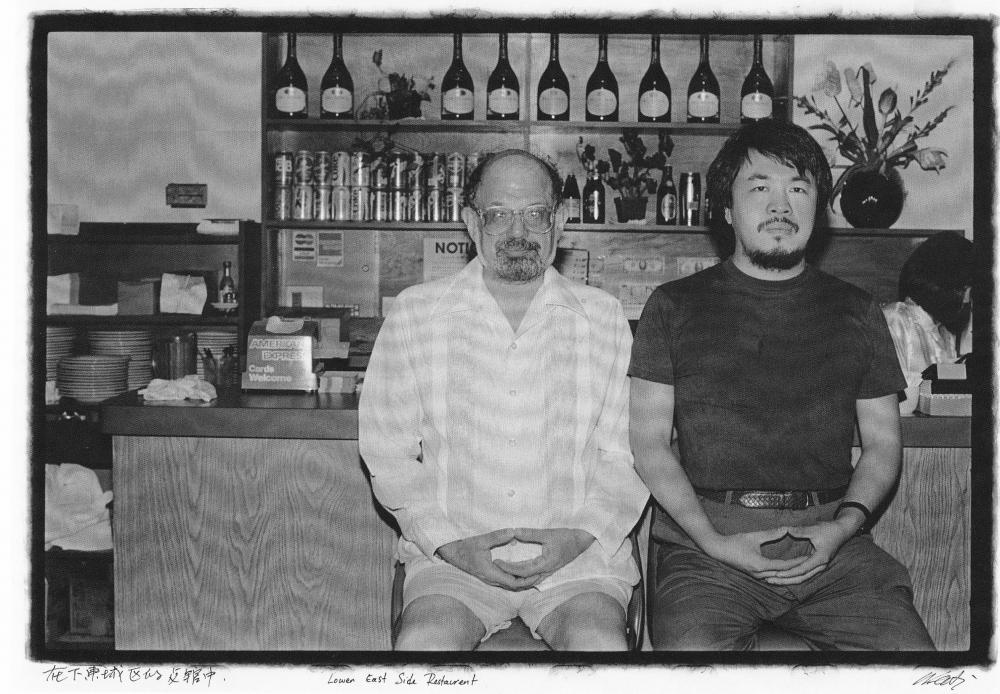

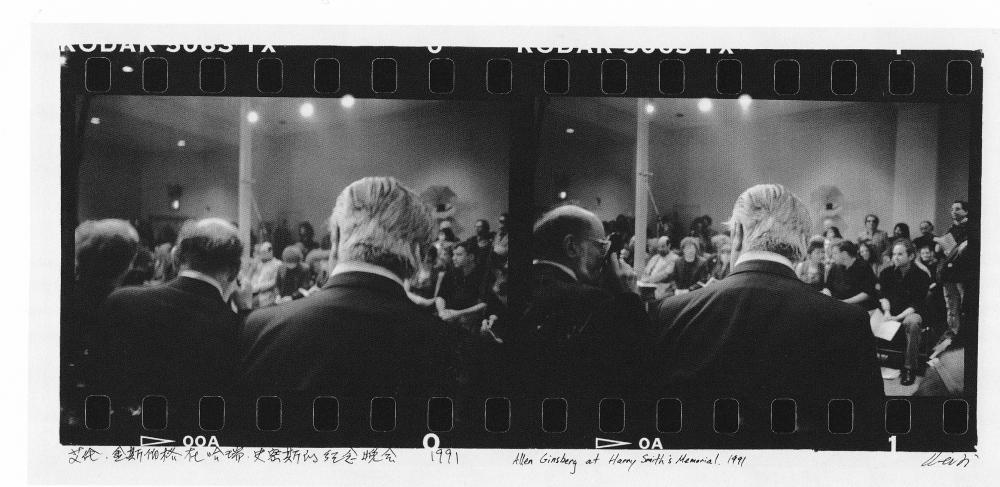

As you might expect, in that case, he was friendly with Allen Ginsberg and Harry Smith

Smith was one of the Godfathers of the beat movement, an artist and experimental filmmaker and bohemian mystic. He was also a fanatical collector of paper airplanes, Seminole textiles and Ukrainian Easter eggs. He would have been living with Ginsberg at this time, having run out of money, an arrangement Ginsberg’s doctor eventually put an end to, the story goes, because Smith was giving Ginsberg high blood pressure.

Ai Weiwei met Ginsburg at a poetry reading at St. Marks In-the-Bowery. Ginsberg knew Weiwei’s father and had met him in Beijing. In the New Yorker, Weiwei describes Ginsberg reading his poetry aloud including White Shroud, which Ginsberg wrote for his mother. “I didn’t quite understand it. But he loved reading it.

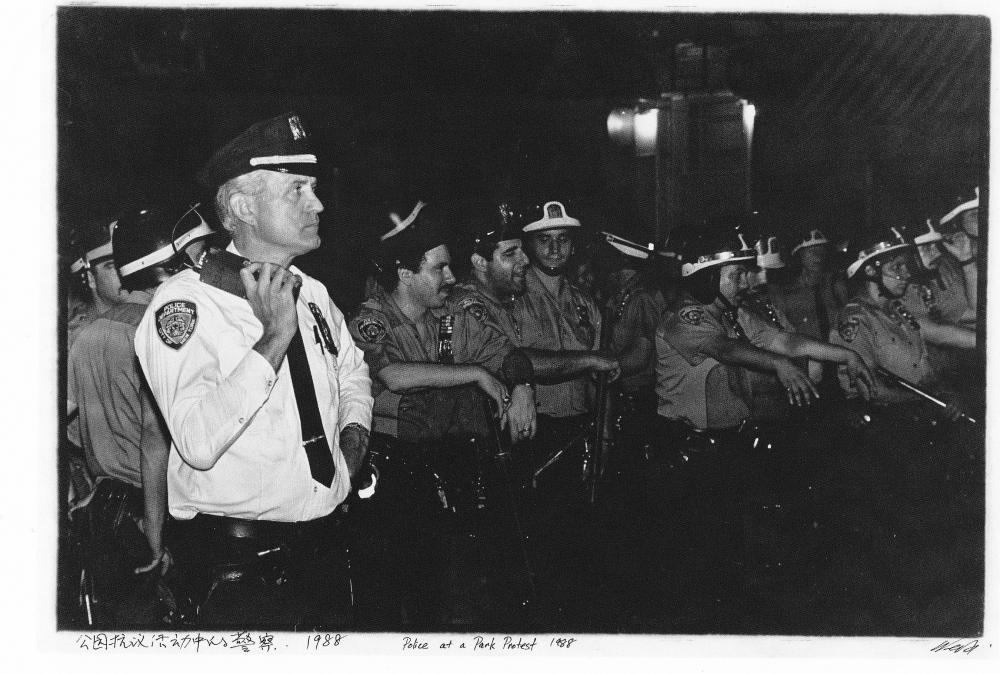

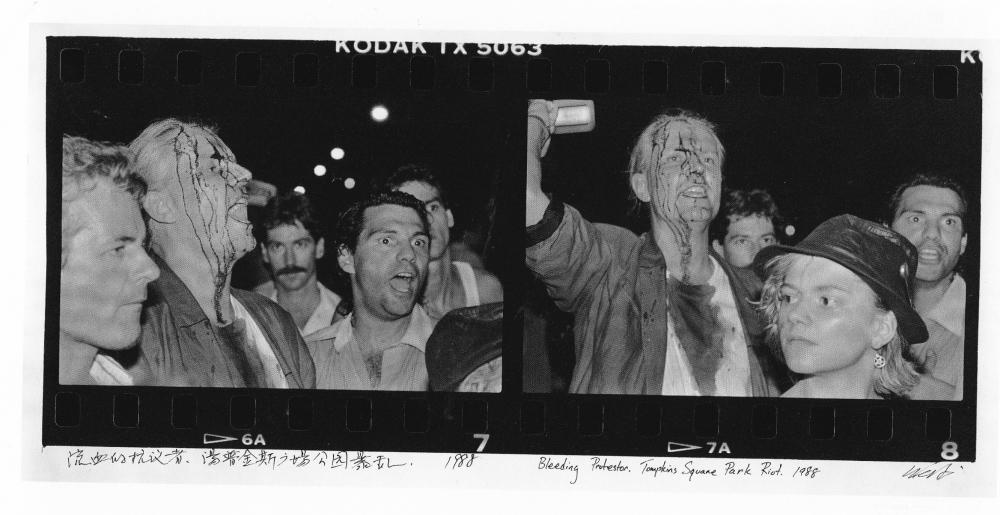

If there was a kind of narrative bump, or turning point in this material, this collection of photographs, to me it seems to be the Tompkins Square Riot photos of 1988.

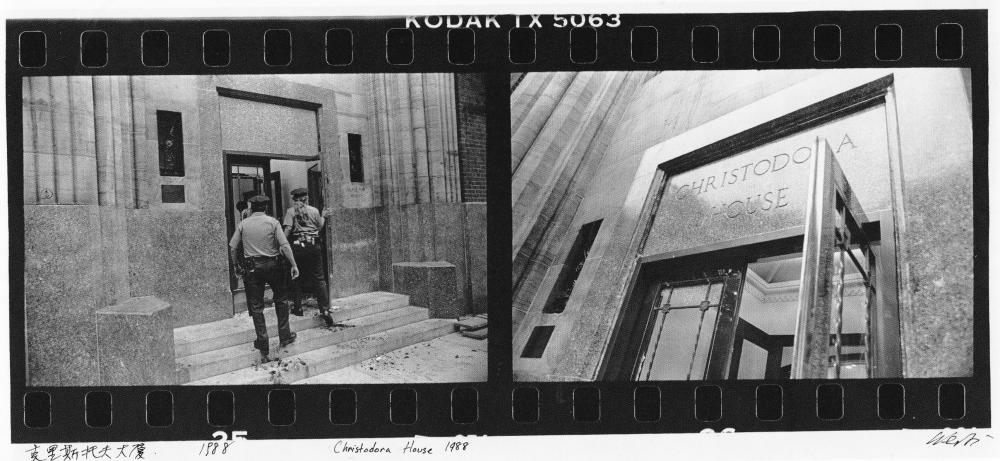

As some will remember, New York had a series of riots in 1988 relating to housing and public parks access. Tompkins Park had itself become a squatters camp which then Mayor Koch famously criticized for being filthy before acknowledging he’d never been there. A curfew was imposed. And on August 6 and 7, police tried to clear people out of the park in what was later referred to as a “police riot”.

This is the front of Christodora House, which is on Avenue B on the east side of Tompkins Park. This is kind of ground zero for the whole dispute. Originally part of the American Settlement House Movement, Christodora House was built in 1928 to provide “low-income and immigrant residents food, shelter, education and health services.” It had a pool and a gym, and was sort of like a private rec centre with social housing. It was in financial difficulties by the 40’s and was sold to the city, who seem to have more or less left it for a couple of decades. During the 60’s it was full of squatters and was reportedly the National HQ of Black Panthers as well as serving as a set for porn films. Wiki tells me that both Iggy Pop and Vincent D’Onofrio at one point lived here.

In 1975, the city sold the property for $62,500 and within a decade the developer began to convert the building to condos, which cause further friction in the area. During the Tompkins square riots crowds broke in and trashed the lobby yelling “Die Yuppie Scum”.

Imagine how angry people would have been if they’d known that in another 20 years, 25 years, a 1400 square foot one bedroom in Christodora would run around $2 million.

Later there would be other protests in Washington Square Park Protest 1988, and Ai Weiwei would be there too.

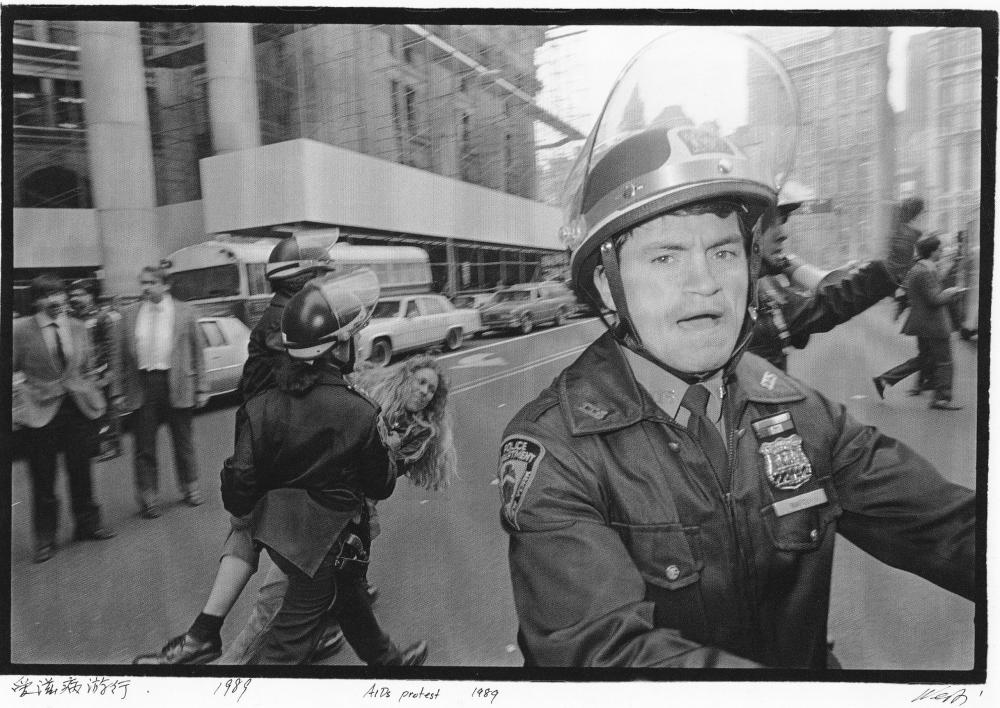

And the following year would be the year of ACT UP AIDS protests.

I think what we’re seeing here is the shaping of a world view, shaping of a sense of skepticism about power. Here’s a young man marked by the cultural revolution, adrift in America, in the process of proving himself to be what his imagination told him he could be… It is probably critical to note that these protests here would have been followed in months by events in Tianamen Square.

Here’s an artist intensely, ferociously engaged I think. Taking stock.

“We were young at the time and soon identified with the values of the free world because of our recent history. We hated totalitarian society very much and longed for the so-called free world. Later, we became more critical of the US when we found out the country didn’t have as much freedom as it claimed.”

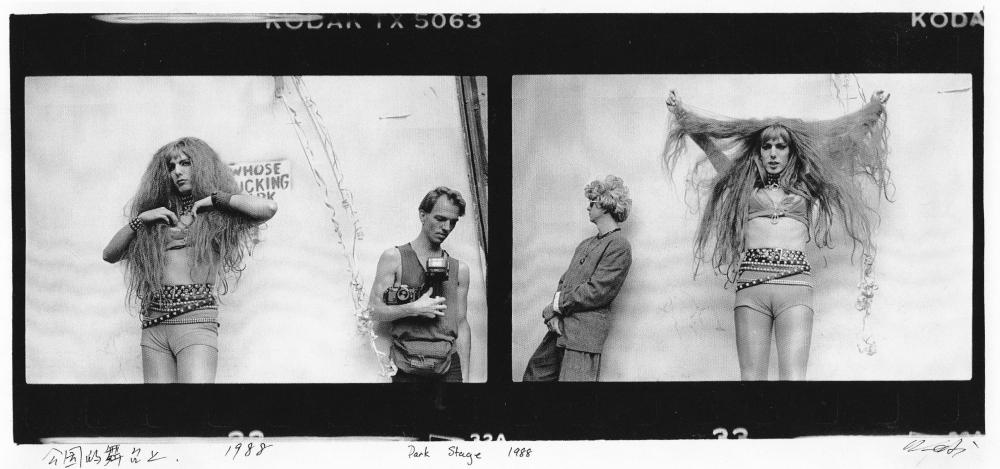

Did Ai Weiwei feel hopeless though? One suspects not. Because woven through the difficult images are always people acting, people (like Weiwei, but in their own ways) claiming themselves.

For every act of suppression, and act of expression.

After 1989, although I haven’t counted them, it seems to me the selfies begin to get less frequent. Ai Weiwei is still present in all of these, but we sense the process of self-discovery is now past its beginnings, that something like conclusions or at least convictions are shaping themselves in this young man.

The future beckons.

The Godfather of Beat Generation, Harry Smith dies

Smith had a heart attack in Room 328 of the Hotel Chelsea. He died in the hospital later in the arms of a poet friend who reported that he was “singing as he drifted away”.

I find myself thinking that Ai Weiwei had an ironic glint in his eye as he selected this as the last of the series.

End credits. Cue the violin. The artist has left the building.

“My experience in the US was the most important experience of my life. There I learned about personal freedom, independence, and the relationship between the individual and the state, as well as the power structure of that society – and art, of course, I learned a lot.”

I want to return to the poet Bei Dao for a moment to close.

This is a short excerpt from Bei Dao’ book Midnight’s Gate about his time in New York. Note that he does not name the artist friend that he meets, but you be the judge who he’s talking about…

“The first time I visited New York was in the summer of 1988. We went to the East Village to look for W…

He’d been living illegally in New York for eight years. People have different reactions to living illegally. Some people live as if they’re walking on thin ice, while others take to it like a fish to water. New York remakes people like no other place.

This man who was a good student – a sophomore in film school – had completely transformed himself. His eyes were gloomy, his face fatter, and his ears bigger.

He was now full of New York slang. As he walked down the street all sorts of people walked over to greet him, their faces full of respect. At that time, the East Village was a land of the homeless, drunks, drug dealers and those suffering from AIDS. He would always grunt a response, but would not say much, just pat them on the shoulder, or stroke their bald heads, and miraculously, their enraged, crazy spirits would calm instantly.

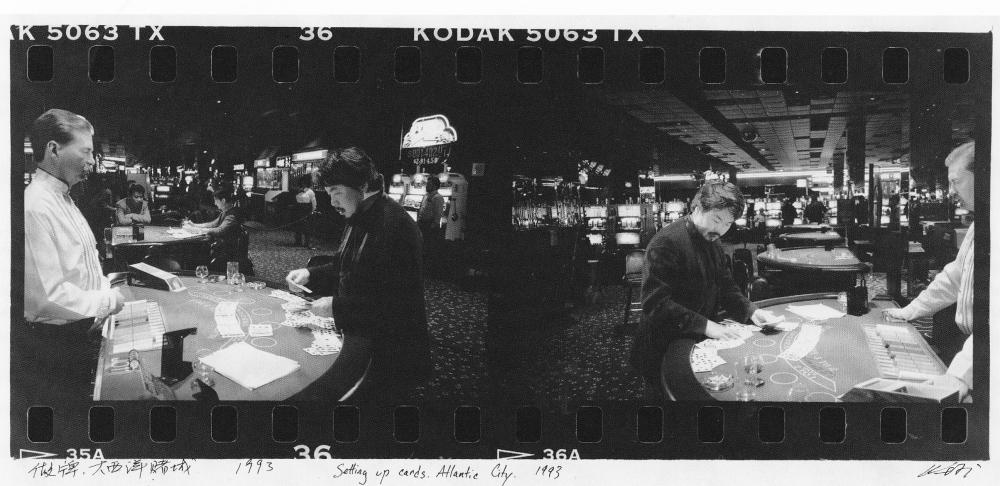

I asked him how he made a living, and he said he painted people’s portraits on the street. He then got out his painting tools, hailed a taxi, and dragged us to a section of West Fourth Street, where a number of other Chinese painters were already trying to drum up business. Unfortunately, luck was not with him that evening as he waited two hours with no one even inquiring about prices. When someone suggested he go to Atlantic City for a little gambling, he immediately closed up shop and sailed off.

I’ll let Ai Weiwei have the last word, a quote which I find resonating in each of these photos. It seems to me that if these photos do one thing, taken all together, it is to show Ai Weiwei reaching this conclusion:

“Creativity,” Ai Weiwei wrote in 2008, twenty years after that visit with Bei Dao… “is the power to reject the past, to change the status quo, and to seek new potential. Simply put, aside from using one’s imagination—perhaps more importantly—creativity is the power to act.”