This article was assigned to me by Gary Ross, to whom I’m grateful. It was one of the most affecting stories I’ve ever work on. And I’m honored to be sharing it with people more widely.

From Vancouver Magazine March 2011

***

It’s an unassuming storefront on a dusty stretch of East Esplanade in North Vancouver, opposite the industrial waterfront. Power Max Auto Repair reads the sign above the garage door which is battered from use. Inside, meanwhile, all the typical sights and sounds of an auto mechanic’s shop: the flash and buzz of an arc welder, the radio playing in the background, the big red box of Snap-On Tools and, of course, the house project car. In this case a 1950 Pontiac StratoChief, which sits in a rear corner of the garage, awaiting the attentions of the proprietor as these are available between other jobs.

It’s an ordinary place, in other words. And yet – through the man who founded this shop, Zahed Haftlang, born in Iran in 1968, a survivor of years of war and torture, and a refugee claimant to Canada in 1999 – it is extraordinary too for the way it connects Vancouver to a critical place and date in Middle Eastern history.

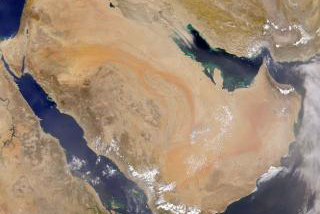

The date is May 24, 1982. It’s called “Day of Martyrs” in Iraq and “Liberation of Khorramshahr” in Iran, both labels referring to what happened that day in one of the bloodiest battles of the Iran-Iraq war, the battle for Khorramshahr. A port city in the oil rich province of Khuzestan in southwestern Iran, Khorramshar was an affluent city before the war. But situated on a crucial waterway, it was also a strategic prize. When the Iraqis invaded in September 1980, Khorramshahr was among the first objectives.

The fighting was brutal. Tens of thousands of civilians are thought to have died in the assault. And despite committing thousands of troops, a lengthy artillery barrage and as many as 500 tanks, Iraq faced tenacious opposition. They took two months to secure the area, losing over 7,000 men in the process. As a result, Khorramshahr became an emblem of resistance to Iranians. In one widely told story, a 13 year old Iranian boy travelled to the city after hearing of the invasion without telling his parents. He fought alongside adult soldiers before being killed disabling an Iraqi tank with a hand grenade. Within months of the boy’s death and the news that Khorramshahr had fallen, thousands of Iranian boys had volunteered. Zahed Haftlang was one of them.

He’d been living east of Khorramshahr in Masjed-e Soleyman. He was 12, and had nine sisters and five brothers. Home life was difficult, especially with his father. One incident in particular spurred him to action. He was caught stealing money from his father to go to the movies. His father punished him by branding his heel with a skewer heated to red hot in the stove. Haftlang recuperated at a friend’s house, where they concocted a plan to run away to war.

Without ever telling their parents, the boys enlisted in the Basij regiment and were shipped out the same day. A volunteer paramilitary group founded by the Ayatollah Khomeini, the Basij was notorious. As John Lee Anderson wrote in The New Yorker: “very young Basijis were encouraged to offer themselves for martyrdom by clearing minefields with their bodies in what became known as ‘human waves’—literally walking to their deaths en masse so that more experienced soldiers could advance against the enemy.”

Haftlang wasn’t asked to do that. He was made a paramedic instead after proving himself less squeamish than his friends. He was appalled by the horrors at first, but eventually became proficient and confident in this work.

In Khorramshahr, meanwhile, 18 months had passed since the Iraqis takeover and the Iranians were now planning for the city’s recapture. Haftlang’s Basij battalion was sent to help. The Iranians had dug a deep trench along the front, the western wall of which – nearest the Iraqis – had been filled with dynamite. To start the attack, around midnight, the Iranians flooded this trench with water from a nearby dam that had been closed and filling for several weeks. Then they blew the trench wall, flooding the Iraqi defenses.

“We thought we were under attack, but it was just the opposite,” Haftlang recalled. “The Iraqis were flooded and their equipment, tanks and troops were ripped away. Many were buried alive in their shelters. The water flowed onto the plains of Shalamcha, leaving behind an army lost in its path.”

Over the next two days, 70,000 soldiers of the Iranian Revolutionary Army fought their way into the city. The youngest and greenest Basiji were held back to use in a second wave, which was unleashed May 24, 1982. Hafltang was among them. And when he entered the city, still under gunfire and shelling, he was tasked with going through a row of bunkers to ensure there were no survivors.

The significance of Haftlang’s assignment was plain. Captured Iraqis were being taken prisoner but, he said, “most of the prisoners ended up dead.” Indeed, various accounts suggest that up to 2,000 Iraqi prisoners were executed in Khorramshahr around May 24th in retaliation for the rape of Iranian women during the original 1980 takeover. Haftlang’s orders were to kill any surviving Iraqi, or deliver him to his almost-certain death at the hands of others.

Hoping he wouldn’t find anyone alive, Hatlang began moving through the bunkers. In the third one he entered – grimacing against the pressing smell of corpses bubbling from decomposition, his small flashlight held aloft for its meager light – Haftlang heard a voice. It cried out. It cried out for mercy. It was a man. He spoke Arabic words Haftlang couldn’t understand, but could intuit. The man said: Brother, brother, we are both Muslim.

Haftlang acted as he’d been ordered to do. He seized the Iraqi’s weapon. Then he stood, his rifle aimed at the helpless Iraqi, poised to fire.

***

Najah Aboud didn’t volunteer to fight. He shakes his head remembering, his hands wrapped around a warm cup of coffee in a shop on Commercial Drive. His memories are troubling and his English is patchy. But he agrees to walk me through the painful story. He worked in a Basra restaurant before the war. He was 21, with a girlfriend and a son he loved very much. He’d been on a trip to Morocco when Iraqi authorities recalled all eligible men to join the fight. “You went,” he tells me. “If you didn’t, there would be big trouble for your family.”

Aboud had military training and was assigned to drive a tank. His division was among those sent to take Khorramshahr in the fall of 1980 and then found itself, in the spring of 1982, facing the Iranian counterattack. They’d been expecting it, so it wasn’t a surprise. But they’d also been expecting reinforcements, which never arrived. And the Iranians came in much greater numbers than Aboud had been told. The Iraqis were overwhelmed. The Iranians, whom the Iraqis heard had been ordered to kill everybody, spilled around the city, pressing right to the Shatt al-Arab waterway. Aboud’s group was cut off as units to the right and left were broken and fled their positions. When his tank was hit by a round from a recoiless rifle, Aboud and his crew were forced to abandon the vehicle. With four comrades, he sprinted for a bunker where other Iraqis troops had taken cover.

They fought until they had no more ammunition. Then, when the enemy reached the bunker, they tried to surrender. They threw down their weapons. They put their hands in the air. But it did no good. Iranian soldiers stormed the bunker spraying arcs of bullets. Aboud saw men falling all around him. “They killed everyone,” he remembers, grimacing. “One here, one there, another one there. I was covered with their blood.”

He fell to the floor of the bunker, literally under the bodies of friends and comrades. He didn’t realize it at the time, but he was himself badly wounded. He’d taken a bullet under his helmet, which had deeply gashed his scalp. He’d also been wounded in the arm. He was losing blood and consciousness. Eventually the firing stopped and the Iranian assault troops withdrew. Aboud lay in darkness. At some point, his eyes blinked open; above him, through the deathly gloom, he saw a light.

“I thought it was an angel,” he tells me. “An angel from space, gliding down towards me.”

His heart began pounding. He thought it might beat right out of his chest. He hardly dared to breath. The figure came closer, down and down until Aboud could see the face of a young soldier. A boy, really. And this boy bent close to stare at him. As Aboud begged for his life, the boy took his weapon and stood again. He looked around, then back to Aboud.

He pointed the weapon down and fired a bullet. Not into Aboud, but into the body of one of Aboud’s comrades laying dead behind him.

***

It was pocket-sized copy of the Koran that did it. As Haftlang stood over the wounded Iraqi, he’d held out a blood-soaked copy of the holy book. When he took it, Haftlang found between its first pages a photograph—a young woman and a small child, the man’s family. And thinking of these loved ones left behind, the young Haftlang suddenly didn’t know what to do.

“I thought maybe that, like me, life had brought him here,” Haftlang recalled. “So I decided to help him, contrary to our orders.”

Disobeying an order was risky at any time. But here—in Khorammshahr, on May 24, 1982, in the pivotal early stages of a brutal war—aiding the enemy would be seen as madness. Treason. Still, Haftlang couldn’t kill the man. And, being a paramedic, if he wasn’t going to kill the Iraqi, he was going to save him.

He took a sample of the man’s blood, ran it back to the medical unit and had it typed, then returned and gave the wounded Iraqi blood. He patched up the man’s head and arm wounds. He got him on an IV drip, using a bayonet to hold the bag aloft. And when the man wouldn’t stop moaning, Haftlang gave him morphine. Then he dragged bodies of dead Iraqis around the man, building a wall of corpses to hide him from view.

For the next two days, Haftlang kept the Iraqi alive and sedated, returning to the bunker secretly between other duties. On the third day, he asked an officer what should happen to prisoners. After berating him for being a schoolboy, the officer decided to check the protocol. He received word that, since the area was now secure, they should begin transferring wounded Iraqis to medical units.

Haftlang went to get the wounded Iraqi and take him to the field hospital. Halfway there they were attacked by an Iranian soldier who struck the wounded Iraqi in the face with the butt of his rifle, shattering his teeth. Haftlang lost his cool. He tackled the Iranian and threw him in the canal.

At the field hospital, Haftlang found a doctor, but he refused to operate on an Iraqi prisoner. After trying vainly to persuade him, Haftlang left the tent and sat on the ground in despair. He said this prayer: “Oh God, you saw how much I tried to rescue this Iraqi’s life, but if you want him dead, it’s your business, not mine.”

A minute later someone came running out to tell him the doctor had relented. Haftlang went to help. They re-dressed and re-stitched the man’s wounds. They worked on his teeth and jaw. Several days later, the doctor called Haftlang back to the field hospital to bid farewell to the Iraqi he had saved. The man beckoned Haftlang close and he bent near the Iraqi’s face, as he had at their first meeting. Only now the Iraqi didn’t beg for his life. He said instead: Allah Salmak, Allah Khalilak. Over and over again. May God protect and assist you. And when the Iraqi tried to kiss the back of Haftlang’s hand – a sign of deep respect in both Islamic and Judaic cultures – Haftlang pulled his hand away and kissed the man once on each cheek instead. They cried together. They embraced. Then they parted.

“An hour later a bus came and took all the captives,” Haftlang recalled. “I don’t know where they went.”

***

Najah Aboud doesn’t know where they went either. He only knows where he ended up—handcuffed and blindfolded, at a prison he remembers being called Sangabest. It was part of an old castle in the mountains close to Iran’s border with Afghanistan. Here, in a dungeon, where they didn’t know night from day, six hundred men were sorted by their captors into groups based on their perceived identification with Saddam Hussein. Those least loyal to the Iraqi leader, and most likely to be persuaded to help Iran, went into a group where supervision would be more lenient. Those thought to be strongly in support of Hussein received the harshest treatment. Aboud was put in that group.

They were interrogated and beaten regularly. In the darkness, on meager food rations, Aboud lost track of time. Only when he was moved to a different prison did he determine, by asking a guard, that nine months of his life were gone. In the new prison, which they called Samnan, nothing changed. Aboud and his comrades had no medical attention, no news, no radio. They were routinely tortured. Sixteen of his friends died in this jail, young men who had been with him in Khorramshahr on May 24, 1982. Outside, the sun rose and set. Inside, Aboud and his comrades endured. Eleven years passed in this way.

When Aboud was 31, he was moved again, this time to a prison near Tehren. He remembers watching jet fighters in the sky through the crack of a window in his cell and wondering if they were Iraqi jets and, if so, if his liberation was at hand. But it never happened. And he realized he didn’t even know if the war was still going on. He had no idea that the conflict between Iran and Iraq had been over for six years, that his country had since fought a costly war with the United States over Kuwait, and that Saddam Hussein had again moved troops into Kuwait only to withdraw when a new American president, Bill Clinton, had scrambled troops to the area.

It was 1994, and Aboud knew none of this and could only hope that one day he’d be freed. Until then, he dedicated himself to learning the language of his captors. He picked up a phrase of Persian here and there until, alone among the prisoners, he could speak with the guards. He was moved again, this time to a prison in Tehren, the Iranian capital, called Hishmate. All the while the interrogations and beatings continued. The deprivation of light, food, human kindness. Five more years passed in cells, in handcuffs, blindfolds, and gags. Until one day he heard the guards speaking of another move. And this time, they speculated quietly among themselves, perhaps these few remaining prisoners – these hard-core cases who’d been captive for seventeen years and still not betrayed their country – perhaps they would now finally be released.

Aboud rode this final bus ride head down, blindfolded, hands bound. His heart was beating hard, as he thought of what the guards had said. When they were led off the buses and their blindfolds removed, he saw that they weren’t in another prison. They were in a large, bright, clean mosque. And there was food—fruit, milk, rice cakes – things Najah Aboud, now 38, had not seen in 17 years.

An Iranian general entered the room and approached Aboud. Tell them in Arabic, the general said in Persian, that we’re taking you to the border and releasing you. When Aboud relayed this news, the Iraqi prisoners shouted and cheered in joy. They surged to their feet. All but one man, an amputee, who had perched in a window after feasting. This man raised his arms in triumph at the news, rolled backwards out the window, and plunged two stories to his death.

They were bussed to the border. And there they made their respective ways home. Carrying his terrible memories with him, the stamped presence of all he had seen and suffered, Aboud went home to Basra to find there was no one left to greet him. His family was gone. Basra had been bombed. There had been wars and events and lives changed utterly while he was away. His girlfriend, gone. His son, too. “The country was upside down,” he tells me. “Everything was upside down.”

It took less than a month to decide what he must do. He contacted his brother in faraway Canada, a brother who had emigrated from Iraq in the distant twilight of life before Khorramshahr. Before the war. As unimaginably far back as 1974. His brother said: “Najah, come join me.” And so another long journey began for Najah Aboud. Into the far distance, and the utterly unknown.

***

For Zahed Haftlang, Khorramshahr was not the end either. It was barely the beginning. He went on to see eight more years of fighting. He was wounded many times. He took shrapnel in his abdomen. He was burned with chemical gas across his shoulders. He was shot through the calf. A bullet tore part of his ear. But he suffered the greatest wound of all after spending time in a hospital unit where he met a young nurse who showed him kindness. Her name was Mina. A few weeks later, after they had decided to marry, she and her family were killed when their home was destroyed during an Iraqi air raid.

Something changed in him. “Mina left me and my world transformed from love and kindness to anger and revenge.” He hardened, grew dark. He’d seen what war could do to people. He knew young men who’d grown compulsively violent, or unreachably depressed, or become addicted to gasoline fumes. His own sickness was anger. After pointlessly killing a prized ram that belonged to a family that had befriended him, he sank into a depression.

On one of the final military engagements of the Iran-Iraq war, in the spring of 1988, Haftlang left for a mountainous region of the Elam province. The Iranians were suffering heavy losses there as a result of an Iraqi operation called “Eternal Brightness.” By the time Haftlang took his position on the front line, most of the Iranian battalion in the region had already deserted. Just days before the UN Security Council Resolution 598 was passed, ending the war, his position was overrun and he, too, was taken prisoner.

Compared to Aboud’s 17-year nightmare, Haftlang’s imprisonment was short—two years and four months. But his experience was every bit as brutal. Instead of Iranian guards, it was Iraqi guards beating him, burning him with cigarettes, hanging him by his thumbs with wire, tearing the tendons in his wrists, executing his friends in the parade square.

“Do you know the meaning of the word ‘captive’”?” he asks. “A captive is a forgotten human who is no different than flies and insects. A captive is a tool in the capturer’s hand, a diversionary instrument, a forced worker, a creature crushed under a soldier’s boots. A captive desires two things. One, death. Two, becoming a pebble or something inanimate and without nerves that feel, eyes to see, and ears to hear.”

When Red Cross agents finally arrived, it was a sunny, hot day in 1991. The Iranian prisoners were escorted onto buses. And when the buses started up, they headed towards Iran, a plume of Iraqi dust rising in their wake. Zahed Haftlang was 22 years old.

***

“How did you get to Canada?”

Najah Aboud thinks and scratches his beard. “It’s a long story,” he says. “Let’s just say my brother helped me.”

I try again: “How’d you feel when you arrived here?”

“Good. Strong,” he says, brightening. He was free here, with no one threatening to beat him or worse. “I feel like I can work all day! 24 hours!”

But then his expression grows serious again. It’s not all strength and happiness, being a survivor. He tries to speak, his voice choked with emotion. He says: “There are bad memories.”

***

Back in Iran, Haftlang did his debrief interviews with intelligence officials, then tried to settle back into a life he hadn’t known in 10 years. He returned to his hometown where his childhood home was still standing. But when he knocked, a stranger opened the door. She invited him inside, but he ran to the graveyard instead, thinking his parents must be dead. There he found a family tombstone. Only it had his own picture on it. Frightened graveyard workers, seeing the man who was supposed to be in the ground, tried to explain that his family had assumed him dead. Haftlang collapsed to the ground with this news.

With the help of neighbors, he did eventually track his family down. They’d moved to Esfahan, south of Tehren. But reunited only proved that old family wounds don’t easily heal. His father and he got along even worse than ever. Having made a pledge to an Afghani man he’d met during the war, Haftlang went to visit the man’s daughters in an orphanage. When he demanded money from his father to support the girls, his father surrendered it, but threw him out of the house. Haftlang ended up homeless and living in an Esfahan graveyard. “It was a dark time,” he remembered. “I had lost my way.”

Still, he used the money to help the girls, and struggled to straighten out his own life. One day at the orphanage, his chance at a new life presented itself. She was 17 years old. Her name was Maryam. She wasn’t a resident of the orphanage; she too was visiting. And when he approached her, he stammered awkwardly his first attempt at civil conversation in a long while. “Do you know the time?”

With sparkling, dark eyes, the young woman said to him: “Well, you’re just out of the jungle, I see.”

Life has its moments of unexpected uplift. Maryam Solaymani was her name. They married and moved to Capadan together. Through a sympathetic friend, Haftlang tried his hand at various jobs. He and Maryam also tried to have children. “But my body was full of shrapnel and chemicals,” he recalled. “My head was full of all the horrible memories of war. I felt depressed and considered my life useless.”

Maryam miscarried twice. Then, on April 24, 1994, shortly after their helpful family friend had intervened again, to land Haftlang a job with the merchant marine, Maryam had a healthy baby girl. They called her Setayesh. Haftlang went to sea the next time as a father, a cause for much happiness.

But the wind was rising. The sea state worsening. Some memories you struggle to lose, and Haftlang’s anger still bubbled within. In Australia, one of 54 countries he visited during his years with the merchant marine, he lost control of it. A Christian priest had befriended Haftlang and a shipmate, and taken them to dinner. Haftlang’s colleague accepted the man’s favours, then assaulted him brutally, leaving him on the roadside. This so enraged Haftlang that he brutally beat his colleague in turn.

There were many ports still to visit. Time stretched like an ocean around Haftlang, who desparately missed home, missed Maryam and his new daughter. He’d reached the depths of depression by the time his ship steamed down an unfamiliar green arm of water, the Juan de Fuca Straight, through whitecaps into Georgia Straight, then towards the pearly glint of a city, nestled on a fold of land at the base of snow-covered mountains, at the lip of a cobalt sea. This foreign place was called Vancouver.

“It was the first time I’d ever come to Canada. I thought about an old saying: when you are somewhere for the first time, your prayers will be met. I looked at the sky from the window and said: ‘Oh God, I’m so tired of my job, of my homeland, I’m tired of these people who behave one way when alone and another with others. I hate everything. I’m sad about all inequalities, all oppressions. Oh God, save me please.’”

He didn’t leave his cabin for days, provoking a violent argument with the “officer of ideology” aboard the ship. The man shouted at him. Haftlang lost his temper. Seizing a picture of the Ayatollah Khomeini from the wall, he smashed it on the deck. It was a fatal error. Now, the officer informed him, he’d go straight to prison on his return home.

Pushed the brink, Haftlang jumped ship. He had $200 and the clothes on his back. He ended up sleeping in Stanley Park, shivering and wet, hating the greenery, hating the rain. He missed the comfort of his dry, brown desert home. Two weeks he lasted. Then he stumbled into a corner store to spend his final 50 cents on food and the Iranian owner recognized him as Persian. Within 10 minutes, he’d been picked up by another Iranian, who arranged a room for him at Welcome House on Drake Street, run by the Immigration Services Society of B.C.

He was safe. He was dry. Within months he had a refugee application pending. But he was 11,000 miles from Maryam and Seteyash and he’d severed all avenues of return. His heart ached. He was sick with the poison of war. In late 1999, alone in his room at Welcome House, unable to imagine a future for himself in this strange place, Zahed Haftlang decided he’d had enough. He climbed onto a chair. He tied a rope to an overhead beam and fashioned a noose, which slipped easily around his neck. Then he stepped off the chair.

***

Najah Aboud knew nothing of what had happened to his long-ago saviour. In 2000, he’d just arrived in Canada, haunted by memories and the absence of his girlfriend and son. He had family here, including a brother and his father. He settled with them in Richmond, which the small local community of Iraqi-Canadians have chosen as their own. There, he’d started up a small moving company.

And he’d started counseling. If you’ve been through years of torture and move to Vancouver, you soon learn about an agency called the Vancouver Association for the Survivors of Torture. VAST, they call it. Founded in 1988 to provide support services to survivors of political violence, the agency is funded by the UN, by Immigration Services, the city and by the donation of time and money by individuals and community groups. If you survive what Aboud survived, you learn about VAST because there is safety, comfort, and the promise of a future there. It was Aboud’s brother who first took him to their offices on Hastings Street, in the bustling stretch just east of Nanaimo.

Aboud remembers one day sitting in the waiting room, idly reading a magazine, when a stranger walked in and took a seat opposite. Younger than himself, but with the familiar haunted air of a wounded survivor, the man caught Aboud’s eye. They nodded and exchanged hellos in English. Then, judging that Aboud came from the Middle East, the man asked if he was Iranian.

“No,” Aboud answered, speaking in the other man’s language. “I’m Iraqi.”

The man smiled. “But you speak Persian.”

“I learned,” Aboud said. “I was in Iran a long time.”

The man was curious. Had Aboud held a government job?

Aboud laughed. No. He’d been in Iran because he had no choice. “I was a POW there for 17 years.”

The man grew serious. Then he chuckled. “Well I guess we’re even, because I was in an Iraqi POW camp for two years myself.”

A moment passed. Then the younger man turned to Aboud again, more intently. He said: “Where were you captured, if I may ask?”

“Muhammarah.”

“Muhammarah,” the man said. “You mean Khorramshahr.”

“Khorramshahr,” Aboud said. Sure. He meant no offense by using the Arabic name of the city.

But the man hadn’t taken offense at Aboud’s use of the Arabic name. He was simply repeating the name as if to make sure he had this detail correct.

“Khorramshahr,” he said to Aboud. “I was there, too.”

***

Zahed Haftlang had stepped off the chair in his room at Welcome House, but the noose never tightened. Just as he himself had appeared like a guardian angel to save Najah Aboud nearly twenty years before, so too did Haftlang have an angel who intervened at the required moment. He stepped off the chair and into the arms of a fellow resident who had burst into his room at the precipitous instant.

After that, it didn’t take long for friends to convince Haftlang he needed to get himself over to VAST. Haftlang remembers going for one or two sessions. Then, on the third occasion, he remembers walking in and striking up a conversation with an Iraqi gentleman who spoke surprisingly good Persian. When the man told Haftlang that he’d actually been taken POW by a young Iranian soldier who’d saved his life, Haftlang interjected.

Yes, he said, he knew that. The incident happened in a bunker.

“You’ve heard my story from my brother!” exclaimed the man.

“No,” Haftlang said. “That young soldier was me!”

For Aboud, whose memories had long been patchy, things were starting to return. Still, his mind could not comprehend the improbability that this man opposite him was actually the angel he remembered coming to him from the sky.

“I held out my Koran to the young man,” he said.

“It had a picture of your wife and son!” Haftlang told him.

“The boy had a light,” he said.

“My flashlight!” Haftlang said.

Now Aboud was on his feet, tears in his eyes, starting across the room towards him. Haftlang stood up himself. He said, “I don’t want to start a fight.”

“If you really are that boy, tell me more of the story.”

“Take off your hat—you have a scar on your head from stitches. And your teeth! You have no teeth here!’”

Aboud was weeping now. Haftlang, too. It all came flooding back. Yes, they had met again in the field hospital. Yes, Aboud had tried to kiss Haftlang’s hand, but he’d pulled it away and kissed Aboud’s cheeks instead. Yes, yes, it was all true. The two men were laughing and shouting and crying together now, embracing, while the staff and clients of VAST stood there, wondering what was going on.

***

In Power Max Auto Repairs, that unassuming mechanic’s shop on East Esplanade, Zahed Haftland sits back in the chair in his little side office and shakes his head. He and Najah Aboud are like brothers now, he tells me. They visit one another’s families. Sometimes go to the movies. “I love him like I love my own son,” Haftlang tells me, speaking of Naiyesh who was born in 2006 to him and Maryam after the family was reunited in Vancouver.

If he could do one thing with his own future, Haftlang says it would be to raise enough money to scour the world and find Aboud’s lost son. Because for Haftlang, while he once saved Najah’s life, meeting the man again after twenty years has saved his own.

“When Najah came into that room,” he tells me, “a new window opened in my life. And my depression disappeared.”

We walk out into the garage. I can hear traffic on the Esplanade outside, airplanes and boats in the harbor beyond. Haftlang has closed his shop for the afternoon to tell me his story, and now he’s going to pull the chain and raise the heavy front door again. And then business and clients and auto repairs will begin again.

But not before he shows me the Pontiac StratoChief. A fine project. He has the engine out now and is rebuilding it. When the whole thing is done, it’ll be perfect, you can tell already. Something from history, something destined for the junk pile, brought back to life and entirely restored. Made new.