My best friend’s name was Sten, as in Stendhal. As in Stendhal Beauregard-Vincent, his father having been important at one point in France. Then he (Sten’s father) had decided to grow a beard, become a boat designer and move to West Van. He designed sailboats for quite a few famous people, including the catamaran that song writer was later found dead in, floating off Passage Island. The one the ferry hit. (That was the same guy who wrote the song Michael Jackson recorded. I can never remember the name, but the tune stays with me. Ba ba, baaa.. etc)

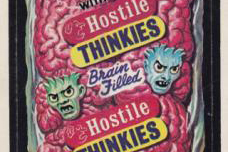

Sten and I, in school and around our street, were known as the Hostile Thinkies. I have theories where the name came from, but no real solid proof. It was from my brothers probably.

Sten’s family lived directly across the street from mine and their house was much more interesting than our house, where my two older brothers, Rob and Scott, and my younger sister Shelly, combined to keep me permanently deprived of space. Sten’s house was all about space. They had a living room the size of a hangar. They had the largest plate glass windows I’ve ever seen in a house. And, bonus, every bathroom (six? seven?) had these sunken bathtubs you could sleep in. We never slept in them but we played cards in the one on the main floor. And Ouiji board once with Sten’s younger sister Mathilda, who had ice blue eyes and could bend her thumb all the way down to touch her wrist.

Despite loving Sten’s house, I have to admit that on several occasions – a statistically anomolous number of occasions, I now realize – we were directly involved in events that nearly destroyed it. I stress that neither Sten nor I ever wanted this to happen. The house was made of almost entirely of cedar. If we’d wanted to destroy it, we could have held a match to one corner. And matches, in my childhood, were like Pez candy. I can’t recall ever being without them. But no, while fire would have been obvious and easy, our methods were always both more involved and weirdly flukey.

One time, to give an example, Sten and I were practicing driving in my front driveway using my mother’s new Volkswagen Beetle. Fire engine red, loved that car. We had a gravel drive at that time, which stretched from the house at the back of the property, down to the street. Sten’s house, which sat low in the trees on the lot across the street, was pretty much in line with the drive.

My mother was always trying to make us eat. Sten was skinny. I wasn’t. But my mother was always calling me in from the woods or from down on the street where, every weekend, weather permitting, there would be a day long game of road hockey going on.

That day, there was a game of road hockey going on, but Sten and I were boycotting on account of one of the big kids who’d threatened to punch Sten’s lights out over one thing or the other. The big kid’s name was Andy, and you’ll hear more about him. Andy thought he was heading to the NHL, among other things. To conclude this from a wicked slapshot in road hockey, which in our case involved a ragged tennis ball and hockey sticks whittled down to rapiers by the pavement, was… well Andy wasn’t bright, even though he was big. And twelve years old.

So we were driving the car up and down. My dad was at work, which he often was on the weekends. And Shelly was at piano. And neither Rob nor Scott had figured out what Sten and I were doing, or they probably would have come out and ruined everything. But as it was, we were taking turns driving the car up to the top of the drive, near the garage, then back it down to the street. Then back up. And at the garage, we would switch. And Sten would come over to the drivers side, and I would walk around the front and climb in the passengers side.

We did this five or six times. Nothing dramatic. We were going slow. Reverse to the bottom. Forward to the top. Switch. One time going up I popped the clutch and the car threw a bunch of gravel backwards, which skipped and pinged down the road, and Andy sent one of his hench-kids up to tell us we were going to get in trouble. But we were on my property. So we ignored him. And I started the car again and popped the clutch a second time, spraying more gravel down the street, and up we went.

Then my mother called from the front door because she had sweet rolls just out of the oven. So in we went to eat these amazing things, which were like cinamon rolls except made with raspberry jam and walnuts. And we spread butter on these and ate them on the deck in the back.. And then we went out front and the car was gone, but a crowd had formed across the street and the police cars were there already.

Nobody saw my mother’s new Volkswagen Beetle roll down the drive. Nobody saw it cross the street at speed. Nobody got creamed. Not Andy or any of the kids playing road hockey. Not Mathilda, who often played with her Barbies in the front yard, right on the far side of the street. Nobody saw the car careen down the driveway, backwards, driverless, bottom out on the pavement, throw up sparks, hit the hedge, punch through, vault off the Beauregard-Vincent’s high stone wall and sail ten feet across their driveway. A flying Beetle. Nobody saw that. But everyone who was outside, anywhere in the area, heard the bang when the Beetle landed. And they all came running to see the car now balanced on the low stone wall out front of Sten’s house, teetering, teetering, the bumper – I swear it, I can picture it to this day – about two feet from the largest pane of plate glass I’ve ever seen in a house. To this day.

Everyone turned and looked when we came out, jam on our faces. Andy, the kids. Two cops, expressions like leather.

Sten and I said nothing. We could have squealed. We could have pointed fingers, said who was driving. Said who did what, left the parking break off. Whatever it was. We were eating jam rolls when it happened. I think we both tried to remember that detail. After it happened, down in the cop shop in Horseshoe Bay, the guy interviewed us. Sten and I kept our story to ourselves. We covered.

“What if some kid had been out on the street?” the one cop asked us.

Long pause. Then Sten said: “Well speaking hypothetically, in that case, sir, that kid would be most definitely dead.”

My dad didn’t get home until much later. But Mr. Beauregard-Vincent drove us home from the cops. We stopped for coffee on the way back. He bought us coffee, which is a thing he did. Little espressos which we loaded up with sugar. He didn’t say anything about the car. He talked to us about Vietnam instead. A bad war. Sins of the fathers visited on the sons.

It was the cop that made him think of it, Sten’s dad said.