I worked on a novel project some years back that involved doing a lot of research into architecture. I interview architects trying to pick up ideas about how they spoke and thought. I walked around downtown Vancouver and central London with different architects trying to get a sense of how they see.

It was all very fascinating and then one day a well-known architecture critic said to: well if you want to get to the bottom of this, you’re just going to have to sit down read the foundational architecture school textbook called Structures: or Why Things Don’t Fall Down, by JE Gordon.

So I ordered a copy. And I loved it from the opening paragraph a lot, which I’ve entered below in slightly abbreviated form:

“A structure is defined as ‘any assemblage of materials which is intended to sustain loads… If an engineering structure breaks people are likely to get killed, so engineers do well to investigate the behavior of structures with circumspection.

But, unfortunately, when they come to tell other people about their subject, something goes badly wrong, for they talk in a strange language, and some of us are left with the conviction that the study of structures… is incomprehensible, irrelevant and very boring indeed.”

That can on occasion seem true of story telling also. You have to build stories the right way, even if when they fall down they rarely kill people.

And here’s another thing I noticed. Check out the cover of my copy of Gordon’s book, purchased for $5 on AbeBooks.

What’s with the skeleton?

And that’s where things get interesting. Because here is something that architecture can teach us about story telling. There is a sense of the structures in play being organically linked to human physiology. And that’s what this blog post is about.

How is that true of architecture?

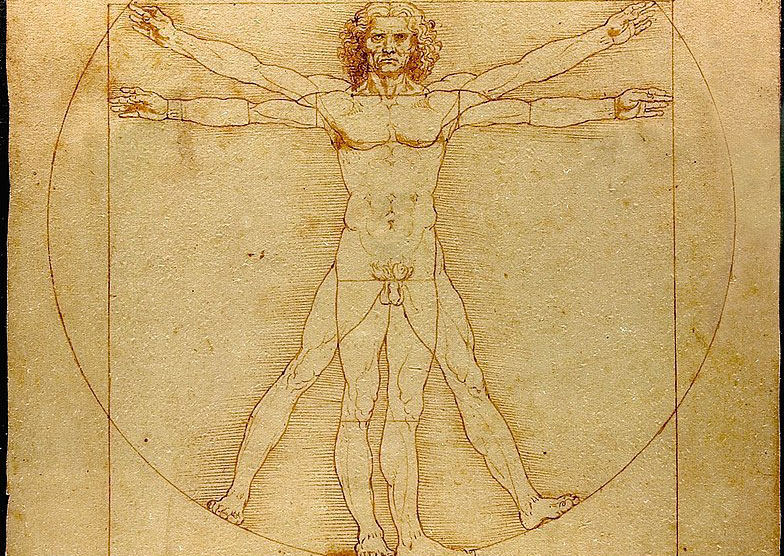

Well we have to go back to another foundational text to see that. That would be the 14th century Italian edition of De Architectura, a seminal architectural book written by Roman engineer and artillery designer Vitruvius. Indeed, the famous Vitruvian Man from the Da Vinci drawing. But Da Vinci wasn’t drawing a portrait, he was illustrating the way that the writing of Vitruvius connected principle building principles and the human body.

The Canon of Proportions, this drawing and its text are sometimes also known. And what a crucial idea it captures: that the human form somehow indicates the principles that should guide the construction of those structures we wish to safely inhabit.

That skeleton on the cover of Structures: or Why Things Don’t Fall Down suddenly makes more sense.

Of course, we don’t build buildings just to stand up. A water tower stands up and is good for what it does. But it’s not a great building in any holistic sense. And here again, with respect to JE Gordon, who himself acknowledges the architect communications do occasionally go badly wrong, Vitruvius is again our source who summed up that holistic expression of what makes good architect in one memorable phrase.

Interviewer: Tell me in your words, Mr. Vitruvius, what makes a good building?

Vitruvius: The end is to build well. And well building hath three conditions: firmness, commodity and delight.

I’m cheating a bit there, because Vitruvius never said exactly that. But that’s how his big idea was translated by Sir Henry Wotton in his book The Elements of Architecture (1624). Firmness, commodity, and delight.

Firmness: Does the building stand up? Does it keep out the wind and rain?

Commodity: An old-fashioned word for “usefulness”. Will people want to occupy the building? Will they find ways to use it for their purposes over time?

Delight: Does the building engage and hold the eye and senses? Is it beautiful?

In short, this:

How is this applied to story telling?

Stories are built things. Stories have architects. Stories have users who occupy them. Stories are sometimes beautiful and sometimes merely riveting and engaging all the while they trouble us. Stories are in every sense a structure. And writers are in every sense the people who wish to do the building.

But more important than any metaphorical talk: stories share with architecture a sense that they are linked to the organic evolution of the human species. For one reason or another, we’ve tended to shape and tell our stories in similar ways over time.

Aristotle famously put that together in a paradigm that is attributed to him and his book De Poetica. That one looks something like this:

From Star Wars to the Lord of the Rings, you can easily discern this shape in storytelling. And I’ll unpack this paradigm in greater length in a future blog post. My point really is that such a paradigm is possible. And it’s not the only one. Other researchers have done similar work, summarizing a historical body of stories to show how they seem to adhere to pattern, as if in response to some organic need or impulse on the part of the humans telling the stories.

Joseph Campbell is another famous example. He catalogued myths told in cultures all over the world. And his schematic summary (which I’ll also blog about it more detail in a future post that looks at the corporate story of Johnny Walker Black) is different in shape than Aristotle, but gestures towards some of the same basic narrative movements.

Here’s how Campbell is typically summarized:

If human organics suggest best practices in building buildings, then these paradigms show us that stories have historically emerged in similar fashion. And if that is an article of faith on my part, accept at least that it has been a useful for me in framing an approach to the craft of fiction.

Returning to that summation of Vitruvius, now bent to our purposes:

Firmness: Does the story stand up? Does it have all of the necessary parts to make it weather the elements?

Here’s where I think the “Elements of Fiction” come into play, those essential building blocks in our fiction: characters types, setting, prose components, style & tone, theme, symbolism & imagery

Commodity: Will readers want to occupy the story and inhabit it over time, putting it to “use” in their own individual ways?

Here we look to the ways that stories have been found “useful” through history, unpacking the paradigms and conventions, not to create rules that mustn’t be broken, but to create an understanding of how narrative spaces have been successfully constructed for reader occupation in the past.

Delight: Does the story engage and hold the senses? Is it beautiful? Or if not, is it yet captivating such that it might achieve the author’s intended effects?

Here in the discussion is where we look to more subjective approaches and techniques, ways to create active and engaged beginnings, accessing characters in ways that make them live, writing dialogue that evokes the real, and the careful building of climaxes, capsize moments and resonant resolutions.

These are all areas which I’ve worked on with students, and which I’ll return to in later weeks and months in my blog.

I hope you’ll join me and share your own experiences with story in the comments sections.