Age and Innovation

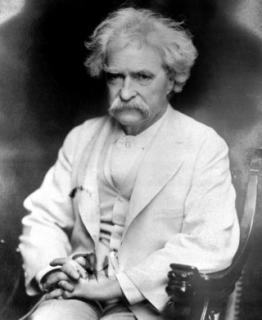

Mark Twain

From the February 2010 Report on Business Magazine

You may have heard rumours that the Mayan calendar forecasts the world will end in 2012. However, the Mayans missed a lesser milestone: In two years’ time, fully half of all federal government employees will be eligible for retirement.

Yes, the work force is aging. There will soon be fewer young people entering the work force than there are older people leaving it. The demographic shift has Stanford economist Paul Romer worried. “Young people, I think, tend to be more innovative, more willing to take risks, more willing to do things differently,” he said in a recent interview, “and they may be very important, disproportionately important, in this innovation and growth process.”

Romer was actually talking about scientists, but the broader implications of his message are clear: A silver-haired workplace may be less committed to coming up with new ideas. Progress, he suggests, will slow.

Kirsten Tisdale, one of the managing directors at Vancouver’s Korn/Ferry International, a major executive recruitment agency, refutes this idea. While Tisdale recognizes that cultural clashes are bound to emerge in the increasingly multi-generational workplace, she doesn’t believe older workers will face a structural disadvantage. Her firm sizes up all prospective hires according to their “learning agility,” not their age. The candidates who thrive, old or young, are thirsty for knowledge, prepared to adapt and equipped to innovate.

Ingenuity is not the sole domain of the young. After all, Newton published Principia when he was 40, and Frank Lloyd Wright gave us Fallingwater-arguably his most impressive design-when he was 70.

In fact, in a series of papers written about innovation and age in artistic communities, David Galenson, an economics professor at the University of Chicago, argues that different kinds of creative thinking happen at different ages. Those who “arrive suddenly at innovations based on new ideas” are often young, writes Galenson, but exploratory thinking tends to happen much later in life. Some of the greatest innovations “are based on long chains of experimentation and therefore usually emerge only after many years of work.”

So, while Orson Welles made Citizen Kane at 25, and Arthur Rimbaud, Herman Melville and T.S. Eliot all produced their greatest work while relatively young, people like Piet Mondrian, Mark Twain, Virginia Woolf and Robert Frost worked well past retirement age.

Moreover, there’s evidence that an aging work force might actually be a boon to some companies. Consider the example of Home Depot, inaugural winner of the Workplace Institute’s 2005 Best Employer Award for 50 Plus Canadians. Faced with staff shortages, the company began hiring older workers who had been laid off from construction and technical trades.

Culture clashes? Not so much. According to Barbara Jaworski at the Workplace Institute, Home Depot found that these workers were more knowledgeable about tools and home renovation practices than their younger employees, and much more interested in sharing their experience.